Click and Collect

The term housing crisis was in use long before Covid-19 forced everyone to down tools. Off-site construction, modular and prefabricated building could make up for lost time but, as Elaine Knutt asks, is it really that simple?

Maps of English towns and cities bear the outline traces of homes that didn’t get built; urban extensions that remained concept studies, mixed-use sites that didn’t stack up. While supply is increasing, reaching 169,000 new builds in 2018-19 (ONS) or 241,130 new homes including conversions (MHCLG), the cumulative shortfall is set against an annual target of 300,000. As we look towards revitalising the economy after Covid-19, awareness is growing that each unbuilt home represents a family in temporary accommodation or essential workers unable to afford a decent place of their own.

But the pandemic has also raised barriers to achieving that housing. The construction sector and wider economy will be restricted by social distancing requirements that create new working procedures, new overheads and new funding uncertainties, along with doubts over whether contractors with weaker balance sheets will be around to deliver projects in the first place. Covid-19 has also proved highly disruptive to the planning process.

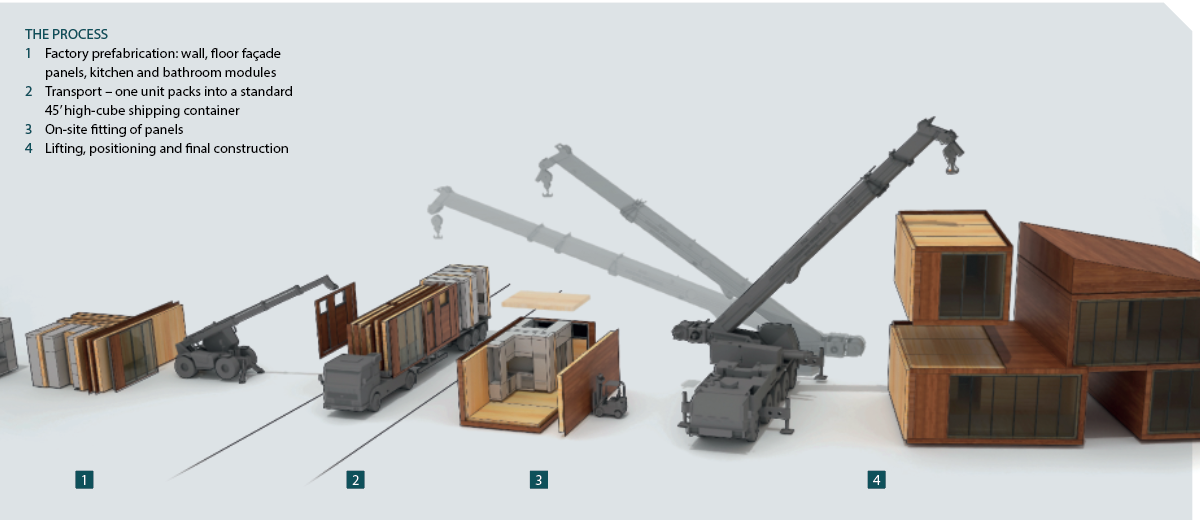

So filling in the map with homes that can be ordered from a factory then trucked to site in one piece (volumetric), or speedily erected from click-and-connect components (modular), looks even more appealing. Homes built using Modern Methods of Construction (MMC) – a label that spans both the above options – hold out the promise of well-insulated, low-maintenance, cost-effective homes for essential workers. Insecure site labour has moved inside the factory environment to create steady, future-proof jobs; digital design and manufacturing can be harnessed to create smarter homes at scale.

The bigger picture

The advantages feed into wider agendas. At a recent webinar held by Building Better, a consortium of housing associations, Housing Minister Chris Pincher MP noted that every 100,000 homes built represents 1% of national GDP, while the improved insulation and air-tightness standards of MMC homes would help to propel the sector towards the ambitions of the forthcoming Future Homes Standard. Mark Farmer, an adviser to the government and official champion of MMC, spoke of catalysing greater resilience in the construction sector and greater collaboration in its supply chains.

At the National Housing Federation, Head of Policy Will Jeffwitz said: “Modular construction can play a really important role in building the homes the country needs, especially social housing. With Coronavirus likely to seriously affect construction rates, it’s important that we’re using every possible route to boost house building to the level it needs to be at. But there are still barriers; for example, there is often a lack of certainty about government funding, which makes it harder for housing associations to invest in research and innovation.”

Helen Greig is Project Director of Building Better, a consortium of 25 housing associations pooling their development pipelines to aggregate market muscle, and she is also anticipating a braking effect from the pandemic. “Every single housing association’s development strategy will be impacted by Covid-19. We think this will be a bit of a catalyst for the off-site sector, as there’s a cliff edge for skills and capacity [in the conventional sector], which brings a lot of problems for sites.”

And if the recession on the horizon follows the playbook of 2008, social housing could be a beneficiary. “The private sector started to talk to housing associations to pass on land and sites, and if that happens again it could be a big opportunity for housing associations,” she says.

As Jeffwitz and Greig note, there are still barriers to increasing MMC adoption to drive housing recovery. Uncertainty about government funding makes it hard to invest in off-site skills and capacity, which holds back productivity. And off-site construction has often repeated the failings of traditional building; with every project viewed as bespoke, manufacturers struggled to offer economies of scale. Can the sector really take advantage of Covid-19 to turn a corner?

Starter for 10

Boosting off-site and modular building is already cast in government policy. In the 2017 budget, it was announced that five government departments would adopt a presumption in favour of off-site construction by 2019.

Homes England currently mandates an MMC specification on around a quarter of the sites it funds, including schemes delivered through the Local Authority Accelerated Construction programme funding. It has also established an MMC Working Group to address barriers to assurance, insurance and finance, and is directly commissioning a number of pilot sites that will use MMC, including 400 homes built by developer Urban Splash at Northstowe, Cambridgeshire.

At BuildOffsite, a lobbying and capacity building group for off-site manufacturers, Strategic Housing Adviser Tom Eshelby empowers housing associations to make good decisions on off-site solutions. “MMC reflects the 21st century and offers a chance to improve some of the issues we got wrong on poor quality housing,” he says. “Homes England is a big tub thumper for MMC, seeing it as a means to accelerate housing delivery and to reimagine the construction industry. Housing associations are being encouraged by carrot and stick – but mainly carrot – to mobilise into MMC.”

The agency suggests that off-site methodologies featured in 2,000 homes in 2017/18, rising to 5,500 a year later and 15,000 last year. Market research company AMA Research calculates that 70% of housing is built in traditional masonry; timber-framed construction of various types makes up 16-18% of the total, while light steel-framed panelised and volumetric systems make up just 3-4% of current output. In total, Senior Research Analyst Alex Blagden suggests that 10% of homes begin life in a factory: significant, but not game changing.

Housing associations and the social housing sector are nevertheless seen as crucial partners for MMC. Grant funded, with strong covenants to raise additional loan finance and less vulnerable than the private sector to market downturns, the sector can provide MMC manufacturers with guaranteed pipelines and the confidence to upscale and invest. Blagden adds: “Private housebuilders could be inclined to stick to baseline building regulation requirements, but social housing providers have a vested interest in the long term, and probably think it is worth it to pay a bit more up front to get a building that’s easier to maintain and with fewer glitches.”

Short-term thinking

However, take up has been hampered by the proliferation of pilots – small projects delivered by housing associations or private developers that capture positive PR and the zeitgeist of the times, but do little to build capacity or knowledge. At Building Better, Greig says: “I speak to hundreds of housing associations, who have all had the same issues with pilots. If they’d spoken to each other, it would have been easy!”

A key difficulty, she says, is the interfaces between groundworks and foundation slabs, and MMC superstructures.

At law firm Clarke Willmott, Partner Zoe Stallard says that MMC projects now account for 25% of her caseload, but pilot projects have fostered short-term thinking, including a willingness to overlook potential legal problems. “People say, ‘we’re only doing a test of ten units, so we’ll just let them go through’. But if it works and you do 250 units, you’ve lost the chance to influence things. Clients are treating volumetric building as something straightforward; but when a modular housing company comes up with a bespoke contract, it obviously protects the modular company not the developer.”

Bespoke contracts tend to be short and unfeasibly optimistic, she says, assuming that nothing will go wrong. “The contracts assume everything will be ok and there are no what ifs? It’s all written in a very positive way, and issues such as delays and liquidated damages just aren’t covered.” Are they storing up issues for clients? “Disputes are probably happening, but on the quiet; they’re not publicised and dealt with by mediation. But defects may take five or ten years to come to light, so it may be too early to tell,” says Stallard.

At BuildOffsite, Eshelby also wants social housing clients to tread carefully. “In three or four years’ time, we don’t want to see families where key workers are left in sub-standard housing because housing associations unquestioningly trusted the manufacturing process and don’t know where to turn when latent defects come into view.”

Building Better is about to flex its combined buying power in the market, going to market in September to seek tenderers for a new framework of modular housing suppliers, consultants and legal teams. However, Greig plans to start small, seeking expressions of interest for an initial programme of just 500 homes. “The current membership are the early adopters; while the majority of housing associations are keen to get on board, but waiting to see proof of concept. So committed pipelines will be higher than 500 units, that’s just the starter for ten.”

Greig says that the sector needs greater certainty from Homes England on future funding: “Under the Affordable Homes Programme, there is no certainty beyond April 2021. We do 30-year business plans and can’t operate on a three to five-year grant programme. With a ten-year grant programme, the sector would invest more, which in turn reduces the cost.”

Richard Harral, Technical Director at CABE: This is not the first time that the government and industry have attempted to stimulate housing supply through use of new technologies, and the problems that have prevented wider adoption of MMC are broadly – if not entirely – understood. In particular, it is recognised that clients and MMC suppliers are trapped in an unbalanced supply/demand cycle that prevents the steady and controlled growth in capacity that is required.

Looking at the market overall it is arguable that the primary problem in sustaining growth in off-site manufacturing is not lack of demand – the UK’s housing crisis means that there is significant appetite for house building capacity. The main problem remains that clients lack confidence in the capacity of the off-site sector to deliver in a timely and reliable way. Clients are nervous about the need to commit to use of off-site at the very earliest stage of development where, in practice, this means committing to a single supplier. For public sector bodies or housing associations, this is of particular concern as they need to be able to demonstrate value for money through open competition.

If clients are reluctant to commit to their use at an early stage of development, the most important benefits of off-site systems are often marginalised or lost. In particular this is a result of planning permissions that are not designed in a way that enables easy procurement through off-site supply chains.

One solution would be to introduce greater standardisation of off-site systems across the sector to ensure that clients and designers have access to a diverse range of suppliers once planning permission is achieved. This wouldn’t remove technological competition or innovation, but would instead focus on linking planning stage design decisions to standardised spatial design characteristics and system parametrics. This would enable a range of manufactured solutions to be chosen to build out the permissioned design.

If greater standardisation can be achieved without restricting competition or value for money, clients will be able to find alternative suppliers if needs be, while manufacturers will find it much easier to maintain continuity of manufacturing activity (because gaps in production can be filled more readily by designs conforming to a standardised approach) – a major step forward in closing the supply-and-demand gap that exists at present.

To achieve this necessitates the off-site and MMC sector setting aside the focus on competition for market share and recognising that collaboration in achieving a mature level of standardisation is in everyone’s interest. It is arguable that sustained growth and investment in MMC to achieve will only be possible once these problems are resolved.

Flatpack homes

Earlier this year, Homes England commissioned a research team – made up of consultants Faithful+Gould and Atkins, with University College London, and the Building Research Establishment – to write a report on eight of its MMC sites to analyse their performance and build confidence in the market. The report aims to provide comprehensive data and insight: on productivity and pace, lifetime costs, the sustainability agenda, and health and safety.

Andrew Prickett, Head of UK Residential at Faithful+Gould and a lead on the research project, acknowledges that in this housing crisis – with issues of an ageing workforce and traditional methods of building – MMC has a golden opportunity. However, he acknowledges that MMC solutions have not always delivered the capital cost savings that were expected.

“A few years ago there was a gap in capital cost, but it’s closing day by day. If the professional team and client team are geared up to deliver MMC, in terms of overall costs we would expect cost neutral or savings. But four or five years ago, we were looking at designs that didn’t work with the manufacturer’s systems and approach, so they had to go back a RIBA design stage in order to go forward. But people are now more informed, manufacturers are engaged earlier in the process and we can get it right first time.”

Eshelby also wants to see firmer data on up-front costs and the long-term performance of MMC homes. “The industry needs to collate more data on building performance. Housing associations are blindly faithful that they will have lower operating costs, but if we can prove that an MMC building will need fewer repairs or upgrades than a conventional one, then its asset value would be higher, which in turn reduces borrowing costs.”

The challenge is not just to match the standards achieved by conventional builds, but to go further, producing defect-free, future-proof homes that will be social and financial assets in years to come. Greig says that MMC’s design potential has yet to be fully released.

“We’re still designing homes the way we did in the 1950s, we’re not designing for today’s lifestyles. When Ikea found that a lot of people were working from home from their bedrooms, they designed a bed that converts to a desk. We should take that kind of opportunity to do things completely differently, designing homes that work from cradle to grave, that adapt around your needs.”

She also wants to see MMC suppliers exploiting the potential for smart technology to identify problems. “We can fit moisture detectors, or sensors that can switch on fans, for ventilation, heating and air quality. In high-rise properties with lifts, you can do an automatic diagnostic if the lift is starting to go wrong. The technology lends itself to volumetric off-site methods, as we can build new technologies straight into the fabric of the building.”

For Eshelby, that means further exploiting the synergies between digital design and manufacturing, rather than using off-site construction to replicate conventional methodologies. “To my mind, if the processes aren’t properly digitised, it isn’t MMC; that’s the sine qua non. Some manufacturers focus on digital design, manufacture, business processes and procurement. But others still talk in the language of construction and architecture, rather than manufacturing and technical design.”

Unleashing further efficiencies from MMC is driving interest in Design for Manufacture and Assembly (DfMA) and platforms. A government-funded project at the Construction Innovation Hub is working with manufacturers, engineers and designers to develop mutually agreed data sets on specification and performance to underpin a suite of interacting building elements for use in residential and non-residential projects. A kit of parts of pre-engineered components, assemblies and products could be installed on site without the need for traditional crafts and trades, such as plug-and-play mechanical and electrical components fitted into a manufactured, insulated and finished wall panel.

Eshelby says that a platform DfMA approach, championed by the likes of design firm Bryden Wood and the Construction Innovation Hub, could become a game changer. “Bryden Wood embodies what architects might look like in the future; driven by the process of production and designing for assembly, where everything clicks, slots or bolts together, and one housing association can buy its design from any number of suppliers.”

At Faithful+Gould, Head of Public Sector Terry Stocks is more cautiously optimistic. “In the future, we may end up with a library of standard panels in stock at various manufacturers, so you can order a house... but we need more comprehensive data on the benefits of MMC first.”

Raising the stakes

There are signs of an influx of corporate finance and investment ahead of future demand. Urban Splash, the innovative Manchester-based developer, last year announced a £22m investment from Sekisui House, Japan’s largest modular housing manufacturer. Developer and manufacturer TopHat secured £75m from Goldman Sachs in May 2019, and Blagden at AMA Research reports that steel-frame off-site company LesKo Modular was recently bought by a private equity firm, Impact Capital, in April 2020.

The arguments in favour of shifting housing production off-site have been in place for years, but – with Homes England exerting its considerable buying power – the dial is shifting. “Longer term, I think growth in the modular sector is inevitable. All the factors weighing in its favour are too strong,” says Blagden at AMA Research. “There is a need for speed of delivery – especially in social housing – with one million people on housing waiting lists time is of the essence.”

Eshelby sees the potential for MMC to come into its own following the pandemic, but points out that its production processes – and business model – will not be necessarily immune to the social distancing requirements.

“The pandemic has brought into focus that good people need good housing; and the need to deliver more key-worker housing might gain political impetus. The government may need to step in and keep local authorities and housing associations incentivised to deliver a percentage of output in MMC to pump prime the industry. But if we can shore up demand, the supply side will take care of itself.”