Building to a head

Every working day in the UK, two construction workers take their lives, according to Office of National Statistics (ONS) data. It’s a shocking statistic, made more so by the fact that very few will seek help for the mental health problems that plague the sector. Now the industry is acting to combat problems that can be exacerbated by what is too often a poor working environment.

Suicide is a national problem. In 2018, 6,507 suicides were registered – the highest number since 2013. Of those deaths, 4,903 were men; this 75% rate has been consistent since the mid-1990s, according to figures from the ONS.

But the building industry itself holds special dangers for its workers. Firstly, 89% of workers are men (who are more prone to suicide) and that rises to 99% on-site, which is itself an environment that provides the means to self-harm. Women are more likely to seek help for mental health problems, while men are more likely to self-medicate. The rate of substance abuse in construction is high and this too is a significant risk factor for suicide.

ONS figures, in its 2017 report on suicide by occupation, reveal that low-skilled occupations had a 44% higher risk of suicide, and even more tellingly, that suicide rates among low-skilled male construction workers were three times the male national average. The risk of suicide among skilled male construction workers was the highest among the building finishing trades, particularly plasterers, painters and decorators – twice the male national average.

Almost half of construction workers (48.3%) have taken time off work due to stress or mental health issues, according to the 2019 Mind Matters survey by Construction News. Of those, over half (54%) hid the real reason, 59% did not receive an appropriate level of support from their employer and 78.3% say there is still a stigma about mental health in the industry.

Workers see long hours, job uncertainty, tight deadlines and financial pressures as the top contributors to poor mental health; with working away, work culture, alcohol, drugs, poor welfare and site safety as other important factors.

Hope is on the horizon

The Construction Industry Research and Information Association (CIRIA) published a guide, Delivering Wellbeing at Site Level, which describes how to improve wellbeing on construction projects and provides a set of tools to help develop a wellbeing strategy.

Its author, Greg Chant-Hall, notes “In the physical environment for example, companies need to make sure the temperature, the lighting, and the furniture is right in the office on a site, making sure that there is space for drying clothes. Everyone is out, exposed to the elements, so when they come back to work the following day, you can’t have them putting on wet clothes. Simple things like this have an effect on people’s perceptions and mental wellbeing.

“Companies need to know how to spot issues people might have, how to have mechanisms in place, [support] telephone lines, friends in their peer group, and champions in the workplace. Often the champions, the Mental Health First Aiders, will be the toughest guys on the site, so we can set the example that this is not a weakness, it’s a strength to come forward to say ‘I’ve got a bit of a problem’.”

The report’s main finding, he says, is that there is no silver bullet; this will be an ongoing initiative that needs to be embodied and integrated into the working practices of every site in the country. The most important thing, because it’s all about people, is the line management caring about their staff, genuinely caring about how they are mentally and how they are physically. This can take an investment both in terms of time and physical investment, and following through on promises and policies that are in place.

“If an employee knows their direct line manager cares about them, plus if they can go to their line manager with an issue and it won’t be perceived as a weakness, but as something that can be addressed, this is going to open up these channels much more. This is exactly what we need in construction, where historically we have had a macho environment, and any talking about feelings is perceived as a weakness. We need to move away from that and the best way to move away from that is better line management.

“If we think about it in conceptual terms, if we put people in an environment where they are cared for and invested in, they are looked after, that’s how we are going to get the best out of people.

“And the converse is that if you put people into an environment where it is very hierarchical, and they can’t be themselves, they have to wear a mask at work, they can’t talk to people, they are in an environment where they’re not invested in, the environment’s not good, the organisation isn’t good, you’re never going to get the best out of somebody.”

A good business, he notes, is going to care about its employees’ wellbeing, and it’s going to maintain its profitability. Most UK companies have a mental health strategy, but some are not exploring the depth of the problem. Chant-Hall said this remark from Dr Justin Varney of Public Health England, quoted in the report, sums up its findings: “Too often, employers go straight to offering yoga and zumba, skipping the importance of a well-defined strategy. You can’t zumba your way out of bad line management.”

Raising awareness

Rev. Kevin Fear is health and safety policy lead at the Construction Industry Training Board. His role is now involved with the increasing mental health problems faced by construction workers, and the CITB has been at the forefront of some of the recent changes. It recently made a £1m grant to Building Mental Health, a voluntary initiative that helps construction industry organisations ‘to raise awareness of mental health issues, promoting understanding, lowering stigma and supporting their employees.’ The money will pay for the organisation to co-ordinate the training of Mental Health First Aid Instructors: some 180 have been trained to date, with the eventual target at 288.

The purpose of training those people is so that they will be equipped to train and pass on the skills and knowledge to be a Mental Health First Aider. Rev. Fear comments that, “For every 20 construction workers, we would like there to be one Mental Health First Aider. We’re a long way from that yet, but that is where we want to be, to take the stigma out of it, to normalise it.

“I think if the industry had tried to do what it’s doing now five years ago, there would have been so much scepticism about it; I don’t think we would have got anywhere. I think we’re starting to push at an open door, because people are realising that we cannot go on with the level of harm that is happening with our workers.

“Traditionally, the construction industry does not have a good image, and it is something that we are trying to change with increased diversification. However, of the vast majority of people we employ on sites, about 98% are men who, when taken away from their homes, without the influences of partners, loved ones and children, can demonstrate destructive behaviours. They have time on their hands; they get bored; loneliness has a huge effect on people on sites, because they are away from their family environment.

“People of my generation – I’m over 60 – when we were brought up, it was ‘big boys don’t cry’, ‘grow a pair’, ‘man up’, and there are still these elements within the industry, ‘we’re tough, we go out in all weathers, we’re doers,’ and to talk about the pressures that we have is a sign of weakness.”

It is not a sign of weakness, he says firmly, it’s a sign of strength. He believes the more role models we have within the industry who are prepared to step out and talk about the problems that they have had and how they’ve overcome them, this then starts to become normalised.

“When I give talks on public platforms, I will always have a small group of people who come talk to me afterwards who say thank you, you’ve just spoken exactly to me.”

The CITB has just awarded £500,000 to the National Federation of Roofing Contractors. It is working not only with roofers but a number of other federations to commission the Samaritans to build an online resilience tool kit that will help promote wellbeing in the construction workforce.

“This is another example of a part of the industry recognising that there is a gap and we need to do something, and I’m so pleased we are working with the Samaritans, because the level of authority they bring is just huge.”

Making a difference

Sarah Birtwistle, Assistant Building Control Surveyor in Guernsey, is one of the growing number of Mental Health First Aiders in the industry. She has helped many people in her new role and is not surprised by the suicide figures for the industry. “It’s something I’m really passionate about; I’m really happy I can support the industry. It’s just as important as CPR and stroke First Aid. With having identifiable Mental Health First Aiders [in the workplace], you don’t have to be in a crisis to seek help.”

Requests for help vary from the complex to the simple, from a construction worker who had lost contact with his son, and simply needed someone to hear how he loved him, to someone in spiralling debt, to a woman who was concerned that her colleague had an eating disorder. Birtwistle advised the father to write a letter to his son, helped the man in debt to do some budgeting and advised him where to get help, and gave the woman some useful information so she could subtly approach her work colleague. On another occasion, a client with dementia had an episode in the building. ”I spent an hour and a half de-escalating the situation, until she felt comfortable enough to leave.”

Importantly, she is trained not to diagnose, but to refer people to someone who can help.

Her training has been useful outside work too. “It’s good for society as a whole to have these members who are becoming Mental Health First Aiders. A little bit of empathy goes a long way; sometimes you just need to listen.”

Visiting family in the UK, she saw a man having a seizure. “It is scary to see someone in crisis, and to approach them. It was drugs. No amount of training would have stopped me being scared. I got him some help, but a year ago, I might have just walked past him.”

Sarah has been in the construction industry for ten years, first taking an apprenticeship as a plumber, and joining the Guernsey Local Authority Building Control five years ago. She’s clear that it is one of the most vital pieces of training she’s had and has become an advocate for the qualification: She is now one of four Mental Health First Aiders in her building; and her son, who is about to qualify as a hairdresser, will soon go on the course himself, with his own employer.

Sometimes it’s easier not to talk. The Construction Industry Helpline App is a collaboration between the Lighthouse Construction Industry Charity, construction software firm COINS and Building Mental Health.

“We recognise that not everyone feels comfortable talking about their feelings or personal situation,” says Bill Hill, CEO of the Lighthouse Construction Industry Charity. “So, the Construction Industry Helpline app is aimed at people who would like to find out more information about how they can perhaps help themselves or if necessary, take the next step in seeking professional help. It is a preventative tool and provides support at the initial stages of a situation so that the problem does not reach a life critical stage.”

Striking a work-life balance

There are increasing numbers of studies being published. Yasuhiro Kotera, Academic Lead in Counselling, Psychotherapy & Psychology at the University of Derby, is lead author for two research papers: Work-Life Balance of UK Construction Workers, and Mental Health Shame of UK Construction Workers, both commissioned by Highway England.

The UK construction industry produces 6% of the country’s economic output (£150bn) and employs 8% of the national workforce, but has many workers who suffer from poor mental health, says the Work-Life Balance report.

The number of construction workers who have experienced psychological distress is more than twice the national average: 55% of UK construction workers have experienced mental health problems in their lives, and 42% of them have suffered from them at their current workplace.

On-site accident deaths have reduced substantially from 200 to 40 in the past 60 years, but the incidence of suicide has been constant at around 300 per year, higher than any other industry, equivalent to 13% of all work-related suicides, according to 2018 ONS figures. And the subsequent costs of poor mental health at work to the economy are estimated to be £74bn to £99bn per year, according to 2017’s Thriving at Work: the Stevenson/Farmer review of mental health and employers, says Kotera.

“Work-life balance is not only about logistical issues; it’s a health issue. It is the strongest predictor of mental health. It is where a worker feels that they are able to perform well in their work domain and non-work domain.

“Work-life balance is not just working less. To some degree, it’s also the perception of the worker: if you like the work, you work hard, but you feel good about it. That good feeling reaches other parts of your life. This is called the enrichment hypothesis. Conversely, if you don’t feel good at work, you don’t feel good at home. This is the scarcity hypothesis.”

Psychological safety, which is also important, is a relatively new concept in work mental health and is a key predictor for productivity.

“Psychological safety means you can trust your workplace and your colleagues to not judge your mistakes; you feel safe to make mistakes, when you do, you feel your colleagues will understand you. If you don’t feel psychologically safe at work, if you feel threatened or anxious or stressed, this can lead to cardiovascular symptoms.”

The Mental Health Shame paper explored mental health shame in workers, masculinity, motivation and self-compassion. Its main findings were that many workers have shame about mental health problems, whereas self-compassion was a very strong predictor for lack of mental health problems.

Yasuhiro notes that after a consultation meeting with managers at Highways England, the findings were reported to workers in a workshop, focusing on self-care and that their feedback was very positive. A further collaboration is being discussed.

The business case for developing wellbeing at site level is clear, and includes benefits such as better performing staff, fewer sick days taken and a lower staff turnover, says the CIRIA report. Many companies can demonstrate the link between improved wellbeing, reduced costs and better financial performance.

Organisations that are adopting a wellbeing strategy may find they have an advantage, says CIRIA. Indeed, there is a cultural shift towards wellbeing and organisations that avoid this issue may lose out to their competitors.

Mental health problems in the construction industry are not going away. But it seems that a tide of compassion and understanding has flooded into the industry, and the result will be better work-life balance, working conditions

and mental wellbeing.

To read the reports mentioned in this feature: CIRIA’s Delivering wellbeing at site level bit.ly/35QUJRf

Work-Life Balance of UK Construction Workers bit.ly/3abtF2I

Mental Health Shame of UK Construction Workers bit.ly/35Rqtph and bit.ly/30sDfcT

If you are experiencing a time of crisis, the CABE Benevolent Fund may be able to help bit.ly/2TwioDU

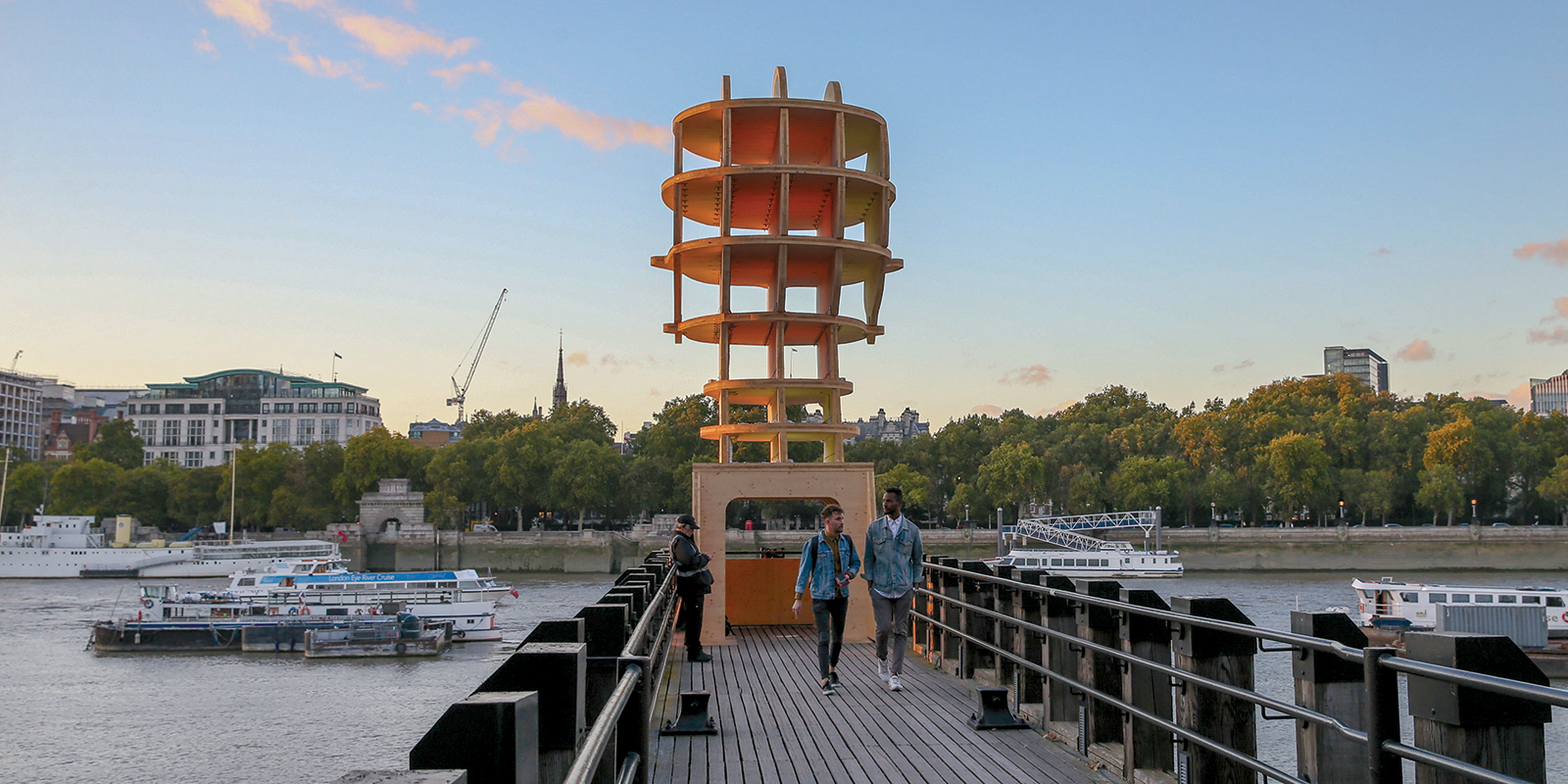

Head above Water

British designer/sculpture Steuart Padwick created ‘Head Above Water’ to support a Time to Change campaign (run by Mind and Rethink Mental Illness) aimed at encouraging more people to talk about issues associated with mental health.

- The sculpture is 9m tall, 3m wide and 4m deep

- It weighs 10 tonnes

- It is made from precision engineered, renewable and sustainable (sourced from PEFC certified forests) cross-laminated timber panels, provided by Stora Enso

- It was designed in four sections, each measuring approximately 3m-5m in width and weighing between 1.5 tonnes and 3.4 tonnes

- It took 15 weeks from concept to delivery

- At design stage, it was necessary to consider the complex logistics of installing CLT panels from the River Thames by barge crane

- The limitations of the crane’s load and reach capacity and its ability to only achieve the necessary height during high tide had to be considered

- Installed by a team of professional riggers qualified to work at height

- The overall installation took just 24 build hours

- It was originally erected at Queen’s Stone jetty (aka Gabriel’s pier) on London’s South Bank

- It is estimated to have had more than 28,000 visitors over five days

- It has since been relocated to a Northfleet site that provides materials and logistical support for London’s new 25km super sewer - under construction to tackle sewage discharges into the River Thames.

- Tideway, responsible for the building of the sewer, has an innovative mental health strategy for workers and works closely with the charity Mates in Mind. Steuart, who visited Northfleet following the artwork’s relocation, said: “I’m thrilled that the sculpture has been rebuilt at Tideway’s Northfleet site. Before I started on the Head Above Water journey I knew almost nothing about Tideway, and it has been a privilege to get to know members of the Tideway community. The care and respect they have for each other is wonderful, and their approach to mental health is inspiring.”

Help points

If you, or someone you know, is experiencing mental health difficulties, there are

a number of organisations that can help:

Anxiety UK

Charity providing support if you have been diagnosed with an anxiety condition. 03444 775 774 anxietyuk.org.uk

Bipolar UK

A charity helping people living with manic depression or bipolar disorder.

bipolaruk.org.uk

CALM

Campaign Against Living Miserably 0800 585858 thecalmzone.net

Men’s Health Forum

24/7 stress support for men by text, chat and e-mail. menshealthforum.org.uk

Mental Health Foundation

Provides information and support for anyone with mental health problems or learning disabilities. mentalhealth.org.uk

Mind

Promotes the views and needs of people with mental health problems. 0300 123 3393 mind.org.uk

No Panic

Voluntary charity offering support for sufferers of panic attacks and obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). Offers a course to help overcome your phobia or OCD. 0844 967 4848 nopanic.org.uk

Construction Industry Helpline

Confidential 24/7 helpline available to the industry’s workforce and their families 0345 605 1956 constructionindustryhelpline.com

Rethink Mental Illness

Provides support and advice for people living with mental illness. 0300 500 0927 rethink.org

Samaritans

Confidential support for people experiencing feelings of distress

or despair. 116 123 samaritans.org.uk

SANE

Emotional support and information for people affected by mental illness, their families and carers. 0300 304 7000 sane.org.uk/textcare or sane.org.uk/support Peer support forum: sane.org.uk/supportforum