Brave new world

Long promised as the key to the future of construction and engineering, uptake of digital advances has been thin on the ground, Elaine Knutt explores why.

The construction industry is on a path to digitisation, lured by the promise that accurate data and informed decision-making will squeeze out its inherent inefficiencies. Under the banner of BIM (Building Information Modelling), software is smoothing out double-handling and scheduling away bottlenecks. Real-time sharing of data and drawings is eliminating errors and co-ordinating different design layers. Safety is also feeling the benefit – lifting an awkward load can be de-risked by gathering the team and digitally rehearsing on screen. Meanwhile, autonomous construction vehicles, guided by 3D digital models, never misjudge an angle or put a banksman in harm’s way. Costain is using artificial intelligence (AI) to fine-tune buildings’ operational performance; Kier is trialling a robot that will patrol and digitally scan sites, checking for progress, deviations and hazards; Turner & Townsend predicts that algorithm-driven scenario planning will revolutionise project management. And then there’s augmented or mixed reality headsets that allow immersive visualisations of digital models and buildings’ digital twins.

But the headlines, LinkedIn posts and Vimeos don’t always address the fundamental reasons for digitisation: the need to increase productivity and reduce carbon emissions, to cut waste and eliminate accidents. On productivity (in terms of output per hour, per head), construction has the poorest record of all sectors in the UK’s economy, and a history of failing to embrace off-site fabrication and standardisation. The October 2016 Farmer Review (Modernise or Die)warned that its lack of innovation, and non-existent research and development (R&D) culture, had left it prisoner to cost inflation, labour shortages and perennial underperformance.

And if there are doubts about the quantity of the industry’s output, there are serious questions about its quality. In the wake of the Grenfell tragedy and Dame Judith Hackitt’s thorough review, the industry has had to own up to poor quality control, poor record-keeping and tendency to game the system. Digital methods are hardly a silver bullet, but they could give construction teams a new rigour and intolerance of errors, as well as the ability to retrospectively interrogate a building record – helping to improve accountability, transparency and standards.

All talk, little action

But how deep and wide does the digital transformation really go? It seems that similar headlines are written year after year, while similar case studies circulate on the conference circuit. On BIM, the principal element in the digitisation change agenda, there is also evidence that the adoption curve is in fact dipping: National Building Specification (NBS), a division of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), has surveyed the industry about BIM take-up since 2011. Its 2019 survey showed a fall in BIM adoption from 71% to 69%, reversing the upward trend from 2015.

Paul Wilkinson, Chair of the Technology Group at the volunteer-led UK BIM Alliance, says that it had originally aimed to make BIM business as usual by 2020, but has now pushed its horizons towards the Construction 2025 targets set in 2013. “I’d say that in two out of three UK projects, BIM is not being used, although survey figures can vary depending on who’s asking and answering the questions. But outside of larger schemes, most smaller projects are delivered using conventional methods.” At Construction Industry Training Board (CITB), Digital and Innovation Lead Marcus Bennett summarises that: “BIM is often used as a design tool, but you don’t see a tradesperson on site with a tablet linked to the BIM model. It exists in part of the process, not across the whole where it has the potential to streamline processes and reporting – and that’s only on the larger projects where it’s mandated.”

Nick Tune, Director at Atkins, also feels that the BIM has failed to reach lower value, run-of-the-mill projects, “You’ve got pockets of absolute excellence, but there’s still that long tail behind. Big flagship projects are starting to adopt BIM properly, such as HS2 and Crossrail. But drop below a certain size, and there’s little adoption – from £15m down I’d say.”

The BIM conundrum

BIM existed as an academic concept decades before the UK government identified it as part of a suite of measures that could squeeze more productivity out of its £15bn-a-year construction spend. By standardising processes, improving co-ordination and reducing the reworking that goes with every handover, BIM promised savings in both capital and operational budgets. In 2011, with the publication of the Construction Strategy and the establishment of the BIM Task Group under the Cabinet Office, BIM became government policy, leading to the April 2016 mandate that construction teams needed to deliver Level 2 BIM on central government-funded projects.

BIM also meant that the extended project teams that struggled to integrate and collaborate would have industry-standard – and government-approved – protocols and processes to bind them together. It held out the promise that the age-old adversarial culture – described in Constructing the Team (1994), Rethinking Construction (1998) and Never Waste a Good Crisis (2009) – could now be repaired digitally by Construction Operations Building Information Exchanges, Common Data Environments, BIM Execution Plans, and Project Implementation Plan and Plain Language Questions. While the language was arcane and the acronyms baffling, the argument that technology could drive culture change and lead to better outcomes was persuasive.

David Philp, now Global BIM Consultancy Director at Aecom, was seconded to the BIM Task Group in 2011. He gives the UK industry’s uptake of BIM a passing grade. “The government set us on a journey almost a decade ago to upskill and build capability, so we were ideally placed with BIM and reforms to government procurement. So [in the UK] we were able to leverage this to create a new trajectory built on this foundation.

“As a result of the UK Construction Strategy, we have indirectly upskilled a lot of the industry, especially SMEs that have become extremely capable in digital modelling and simulation. Other countries have also gone on a BIM journey, but the UK has done it consistently with a focus on information management, better data exchanges and data security, and doing it in a collaborative manner.”

The 2019 National BIM Report from NBS agrees that many promises have been delivered: 60% of respondents reported operational and maintenance savings, 55% saw faster delivery and 81% reported better co-ordination of construction documents – although it’s perhaps telling that only 48% reported an increase in profitability for their own firms. However, only 22% believed that the industry is delivering on the government’s mandate, and just 32% of respondents believed the government had maintained momentum since 2016.

John Eynon, an experienced Design Manager and BIM enthusiast, who is currently working on mid-tier projects run by mid-tier contractors, has also seen a mixed picture. “Certainly, most of the Tier 1 [contractors] have got some sort of digital strategy and delivery in place. But I worked with a contractor last year that was deliberately avoiding BIM; they recognised they would have to deal with it sooner or later, but even without BIM they were getting work and were actually quite successful. As for the supply chain, the steelworks specialists, services contractors or cladding companies are really on the ball, but for the others it’s a mixed picture.”

Now, many see BIM as just one aspect of an ongoing digital transformation, and a need to re-focus on aligning construction with mainstream digitisation. “BIM is disappearing as a phrase, the agenda is now about digital construction or better information management,” says Atkins’ Nick Tune. Taking this argument to its logical conclusion, he believes that the sector must ultimately re-shape itself around the technology. “Design needs to follow the software industry, so teams would have agile design development, where everything is overseen by the scrum master. It will change everything, and we’re currently mid-shift.”

May Winfield, an Associate Director advising on legal issues in the commercial team at BuroHappold Engineering and recognised BIM expert, also feels that the future lies in exploiting a range of technologies beyond BIM. “Other innovations will help [drive digitisation]: drones, modular construction, AI and autonomous vehicles will all become the norm, so digital will become the obvious choice. Four or five years ago, when I was going to conferences, it was all technical such as how to use REVIT. October’s Digital Construction Week was all about future thinking, how do we integrate it all, what’s next? Now that we know how to use the tools, how do we make this better?”

CITB three-pronged programme

At the CITB, Future Skills and Innovation Lead Marcus Bennett is also looking ahead, to an era where an autonomous plant is programmed on-site, factory-engineered components can be assembled by robotic devices, and AI and algorithms can ensure buildings operate optimally or even generate different design options. “We’re moving to a future where we have autonomous machines and plant and AI, and part of an individual’s job moves from doing something themselves, to setting the parameters for a computer or a machine to do something.” But, as he acknowledges, there’s a problem. “The structures to enable this are missing.”

Bennett believes that the current lacklustre take-up of digital technologies outside the industry’s top tier – and the resulting threat to the take-up of emerging technologies – can be linked to a collective insecurity. Where there are multiple bodies advising on BIM, but no clear codes, training routes, qualifications or standards to follow, there is doubt, confusion and an incentive not to take action. The NBS report backs him up: asked about perceived barriers to BIM, 63% and 59% of respondents respectively cited, “lack of in-house expertise” and “lack of training”.

“Despite the fact that construction does amazing things, culturally it’s a risk-averse industry,” Bennett says. “There is no visibility of supporting structures and a lot of the support that is there isn’t great. A lack of leadership knowledge and drive, clear standards and appropriate training slows things down.”

The CITB, having explored the issues in its October 2018 report, Unlocking Construction’s Digital Future, is now putting in place a three-pronged approach to digital upskilling. Firstly, in recognising that business owners and directors can most effectively instigate change, it is providing £1m in funding six projects – varying in scale and target audience – to “put in place training, structures and processes to introduce construction leaders to digital skills and demonstrate the benefits of digitalisation and share it widely.” The initiatives are being run by the Supply Chain Sustainability School, Willmott Dixon, Leeds Beckett University, the National Federation of Builders, Gloucestershire Construction Training Group and Setting out for Construction, a training organisation for site engineers and surveyors.

Secondly, it is inviting bids from consultants or academic partners to draw up a Digital Competence Framework (DCF), defining the skills that site technicians, project managers and nine other job categories should have in tomorrow’s industry. Should a site manager be able to take responsibility for setting up site-wide wifi? Or manipulate the code to operate an autonomous crane?

From early 2021, employers, training providers and individuals will be able to check the framework, where job roles will be cross-referred with multiple specific competencies under six headings: digital literacy, or using devices; data security for connected devices; design and development, data capture analysis and insight; modelling and simulation and smart construction and built assets, including Internet of Things (IoT) sensors and connectivity.

“It will be a 3D structure covering core competencies, job specific competencies, and behavioural competencies, from bricklayer to civil engineer,” explains Bennett, adding that the £800,000 initiative has received support and encouragement across the sector. “The big Tier 1s, and the trade federations representing the smaller organisations have a sense that this is something positive. But with hindsight,

it’s a shame we couldn’t have started it several years ago.”

When the DCF is completed, or drawing near to completion, the CITB will then launch a £1m search for training providers that can devise training programmes to deliver some of what they view as the priority skills described. “The DCF will give us 100s of permutations of statements, and then we go out to the industry to say ‘please try to meet what you see as the most important of these’. We’re putting in place the standards that will be required now, and in the future with the hope that this will provide one important component to help improve productivity and capability.”

Castles in the air?

While the government now sees BIM adoption as an industry-led process, it has thrown its weight behind the idea of digital twins for every building and piece of infrastructure, each digital entity sharing data with its cyberspace neighbours to create a nationwide digital twin. The initiative originated in a report from the National Infrastructure Commission, Data for the Public Good, and is being led by the government-funded Centre for Digital Built Britain (CDBB), based at Cambridge University.

The proposal is that smart buildings, roads and public spaces, fitted with IoT sensors, will have a 3D digital model connected to real-time data on their usage patterns, energy performance, air quality, number of visitors or other points of insight. Local authorities, transport planners, energy networks or building owners can option different scenarios to optimise performance and usability. However, it would also be possible to collect and exploit such data without creating a 3D visual representation as a user-friendly wrapper. Is the CDBB programme really just building digital castles in the air?

Aecom’s Philp, a consultant to the CDBB, asserts the value of digital twins, and says that several AECOM clients are already investing in them. “It’s not just new assets, but at portfolio level; creating models of the retained estate to support operational aspects for forward financial investment planning, and insight to predict and shape optimised repairs and maintenance. We’re going on a journey with these clients, we’re building on BIM by connecting [real-world sensor] systems to get digital data flowing between the two, then analysing and acting on it.

“BIM is a footprint, and now we’re building on top of that by connecting our digital models up to the physical assets and measuring their operational performance through advanced data analytics. In the hospital sector, for instance, clients might want to look at daylighting and ventilation, the number of air changes, infection control and then also healthcare informatics – the data for patient recovery rates and patient outcomes. All these data connections give you extra insight and ultimately better user outcomes.”

At the practical level, Philp predicts that the main contractor will create the as-built digital representation, and install all the smart devices and building controls. Then, the client’s estate and facilities management team will work with an integrator to configure and curate the digital twin.

He adds that digital twins need to be populated with an appropriate number of data sources aligned to the decisions it needs to support. “The level of connectivity might be different for an acute hospital compared to a GP’s surgery”, for example.

There are also predictions that project stakeholders will be able to interact with digital twins by using augmented reality headsets, such as the Microsoft HoloLens. With an app linked to the 3D modelling software, users would be able to walk around a hologrammatic version of the model, reaching out to interact with digital elements.

Not everyone is convinced, however, that we need a world of digital doppelgängers. Winfield said she’s heard of a jokey proposal to set up a ‘Digital Twin Appreciation Society’, a tongue-in-cheek acknowledgement that digital twins are more rumoured than encountered. “There is an official definition, but no one can quite agree what it is and how you get there. The idea of live information and different buildings talking to each other is amazing, but wouldn’t there be GDPR issues? It’s a bit like the questions everyone had on BIM at the beginning: why are we doing it, and what data do we really need?”

At Atkins, Tune can see the potential. “A digital twin is only a digital twin if there is a connection between the digital and the actual, otherwise it’s just a design model. With Cardiff University, we’re working on technology that uses AI to learn how the infrastructure is performing, to provide useful insights, for instance, on the energy performance of building. The model would collect data from IoT sensors, then the AI would understand and optimise the data and come up with optimal solutions to reduce consumption. Imagine if we could do that on a citywide scale.”

Grenfell and refurbs

Digitisation in construction will be given an additional boost by the post-Grenfell regulatory environment. The Hackitt Review was launched in the wake of a fire safety testing programme that laid bare how design data and as-built buildings often fail to match up; that new buildings have been constructed with age-old workmanship problems; and that many building owners simply didn’t know the risk factors in their property portfolios. Its recommendations will mean that a Golden Thread of building information will be required for all new and existing Higher Risk Residential Buildings (HRRBs) over 18m.

According to one Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government estimate, there could be 11,500 buildings in scope – and more if the scope of the new Building Safety Regulator is widened. “The Hackitt report is making people sit up and take notice. Unfortunately, sometimes people have to be obliged to do the right thing if there is a cost and no guaranteed return,” notes BuroHappold’s Winfield. “Regulation is often a powerful driver for people to change their systems and methodology,” agrees Wilkinson.

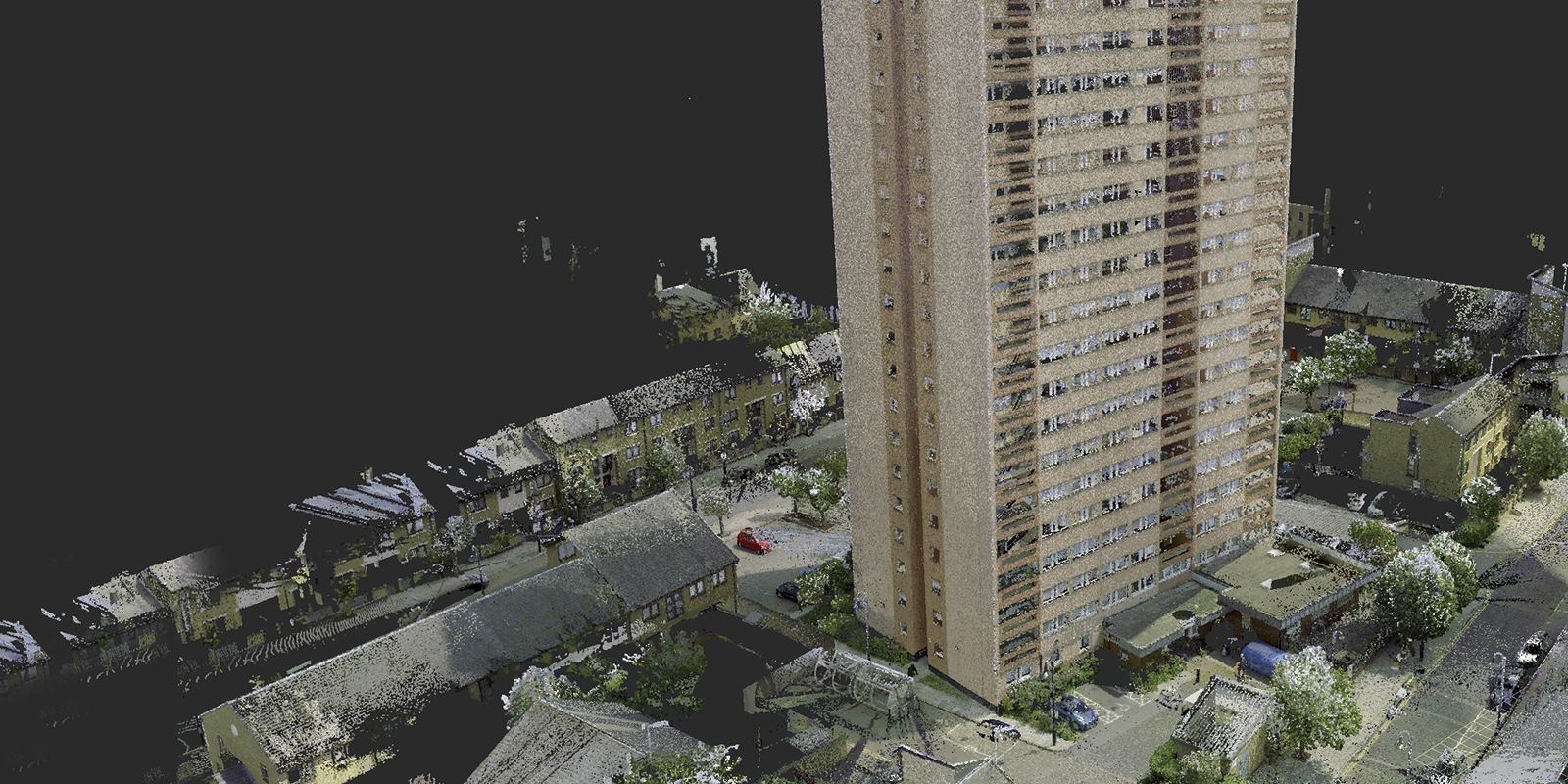

To retrospectively create a digital record, where there is no 3D BIM model, owners and consultants can turn to laser scanning or photogrammetry to create the foundations of a digital model of their building.

Describing the latter, Wilkinson says, “You take 100s of photos of a building, then software stitches them together, so you can get a photographically faithful representation of the building as it stands. In a refurbishment, it can be a first step before starting design work. You can also link it to an asset management database, and visually tag every element in the model.”

In one example, described on bimplus.com, digital novice Clarion Housing Association, completed a golden thread digital record for a Kent tower block by creating a laser scan and then building a 3D model linked to a database of asset information. With little retained information about the 1960s-built Bekesbourne Tower, a 12-storey concrete frame block in Orpington, Clarion’s technical team hired a Leica BLK360 scanner for £800 a week. It took both laser measurements and photogrammetry at the same time, creating a digital representation accurate to 1mm over 60m.

Philp also emphasises the advantages to accountability and transparency of such technologies. “Having an actual 3D digital representation would be a huge asset. It becomes a vital asset management tool; if there was a trigger event, you could interrogate the model and database.

For instance, you could use it as a basis for helping to validate that the fire stopping has been installed properly. You could build the model retrospectively or as the building progresses and have a complete as-built record.”

“With safety cases, we’ll likely see a need for more rule-based checking, and more automated checking to help evidence compliance. We’re also seeing a new-risk appetite from investors and clients, who now want to be certain their assets are fit for purpose and meet statutory requirements.”

Digital future?

With the digitalisation of construction, the scale of the challenge is equal to the value of the prize. Construction is still notoriously fragmented: the CITB’s Bennett emphasises how more than 97% of its organisations are SMEs or micros, 40% of its workforce is self-employed and 40% of its spend is actually on repair and maintenance of the existing stock. Meanwhile, the industry operates in multiple locations; project-based work means that successful teams disband and have to be reformed; expertise never becomes consolidated, and the complexity of the process inhibits many from adding more complexity.

At Atkins, Tune agrees that construction is actually hard to disrupt, but believe it is on a journey of incremental improvement. “Everyone’s looking for the next Uber or blockbuster in construction, but I don’t think it will happen. Construction has multiple different clients, complicated projects with broken supply chains, and isn’t easy to disrupt compared to taxis or shopping. We’ll see lots of smaller disruptions, not one huge disruption. It’s about streamlining processes and making them smarter, understanding the data and automating the mundane repetitive bits.”

The CITB’s Bennett is also optimistic that the industry has the capacity to meet the challenges of the future. “We have a very complex built environment. But with better processes and better technologies, we can improve productivity and get better at achieving sustainability targets and net-zero. At the CITB, we are investing £3m in a digital construction strategy for an industry that accounts for 8% of GDP and 9% of employment. We’re trying to take some risks today that other people might have difficulty making. But hopefully the impact will be counted in tens or hundreds of millions of value back for the construction industry in the years to come.”

Skills and training

There is widespread agreement that the industry’s digital transformation needs a better supporting infrastructure. “Most [academic] BIM training is at post-graduate level, but we need to see a better introduction of BIM and digitisation into undergraduate programmes and across all disciplines,” agrees Aecom’s Philp. “We need new entrants who are digital natives, we need all our apprentices and graduates to have appropriate digital capability. Whatever your role in the industry you will be either producing or consuming data, it binds us all together. Also the UK education system is very knowledge-based. In other countries, it’s more skills-based. So, can you code? Can you connect and integrate siloed databases? We need to have more focus on practical skills.”

At Atkins, Tune agrees: “Generally, the younger generation are engaged and enthusiastic, and the top layer understands the need for change. The CEOs understand the business opportunity, and the better graduates want to make it happen. But for the layer in the middle, this whole programme won’t be quick. People are more receptive, but it’s about getting the right structures in place. There’s a lack of knowledge and skills out there, the whole industry is struggling,” he concludes.

The UK industry does have some advantages, however. It has given the world the BS and PAS 1192 suite: standards setting out how to produce, share and secure BIM data. Now the world has returned the favour by devising ISO 19650, an international standard that draws heavily on the original British documents. Winfield, who recently led a team drafting industry guidance for the standard, believes that ISO 19650 will be a game-changer, launching a ripple effect that will push analogue-only businesses to the industry’s fringes.

“The BS 1192 standards have standardised the process, and now ISO 19650 will slowly replace them. Tier 1 contractors will start to say ‘you must adopt this’; already more and more tender [questionnaires] have a section that asks whether you have BIM certification,” she says. “The UK are the leaders in this field: when I did a keynote in Berlin at a BIM conference, and at another conference in Portugal, both acknowledged that the UK is several steps ahead.”

Image credit | iStock