A brief history of building materials to the present

Mud bricks

From mud bricks to smart concrete, Instarmac gives a brief history of how building materials have changed over time.

Did you know that concrete is the second-most consumed material in the world – second only to water? One of modern humanity’s most important innovations, concrete has brought home construction to new levels, supported sprawling cities and facilitated structures previously thought impossible. And, with the news that Nasa researchers have been working on waterless concrete for 3D printing on the Moon, it seems concrete might be about to play another huge part in the advancement of the human race.

Bricks and concrete have been used side-by-side for centuries, but how did we arrive at today’s construction standards?

7500 BC: Mud bricks

It’s fair to say that bricks have been around for a while. The oldest bricks discovered to date can be found at Tell Aswad in Syria and date back to around 7500 BC. These bricks were shaped with clay or mud and left to dry in the baking sun, allowing them to become sturdy enough to use in the creation of dwellings.

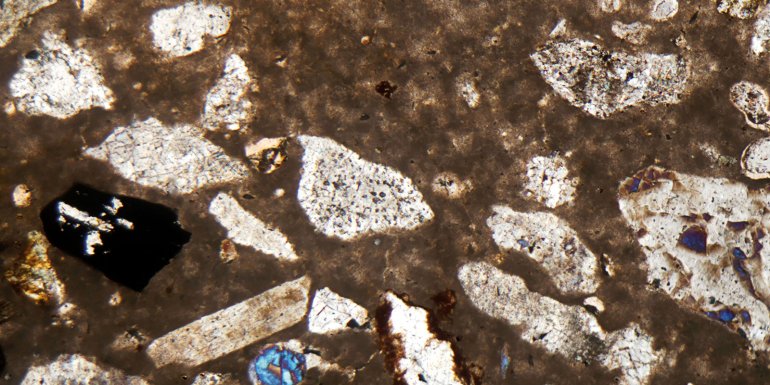

7000 BC: Concrete

While concrete might appear to be a newer phenomenon, we can trace the earliest concrete structures back thousands of years. Early concrete, made by mixing quick lime with water and stone and leaving it to set, was found in a hut in Israel that dated back to 7000 BC.

Knap of Howart

Concrete arrives in the UK

3700 BC: Knap of Howar

The oldest house found in the UK is thought to be the Knap of Howar on the island of Papa Westray in Orkney, Scotland. This home was built with local stone, as are some of the other earliest dwellings from across the country. This indicates that the UK’s earliest homes were most likely built with the sturdiest materials their occupants could get their hands on.

43 AD: Concrete arrives in the UK

The Roman invasion of the UK in 43 AD heralded the arrival of new advances in infrastructure, from roads to walls for homes and cities. The Romans brought concrete that was far more advanced than anything previously available in Britain and developed building techniques that would create a smooth finish while protecting the building’s concrete core.

However, when the Romans left the UK in 410 AD concrete left with them and the recipe was lost. It was later revealed that Roman concrete’s strength came from its use of pozzolana, a type of volcanic ash found in Italy.

Wattle and daub

Bricks are back

1200-1500: Stone foundations or wattle and daub

Without Roman concrete for housebuilding, the UK’s homes took something of a step back. Early medieval city dwellers used a combination of stone, chalk and flint to build their homes and created thatched roofing with dry vegetation, such as straw or reeds. After a huge fire in London in 1135, however, it was decreed that no more new homes would be built using thatched roofs.

Under Elizabeth I, timber framed buildings with wattle and daub infill were primarily used for home construction (daub is a mixture of wet sand, clay, dung and straw). This construction method provides the foundation for many of the Tudor houses remaining today.

Though wattle and daub construction declined in popularity over time, it remained a viable construction method until the 20th century.

1500-1800: Bricks are back

Throughout the 17th century and beyond, bricks were back in vogue. Used extensively in the rebuilding of London after the Great Fire of London in 1666, brick-making had become a respectable, regulated trade. Techniques such as Flemish Bonding characterise the work of that time.

A number of significant buildings using Tudor brick remain from this period, perhaps most notably Hampton Court Palace.

Portland Cement

Brick-making at scale

1824: Portland Cement

It wasn’t until the 18th century that engineers took up a renewed interest in concrete, trialling new compounds to increase stability and durability for the demands of the modern world. In 1824, a huge breakthrough in Leeds changed everything.

Bricklayer Joseph Aspdin patented Portland Cement. He named the cement after its resemblance to Portland stone, the ingredient that would eventually constitute the base ingredient of today’s modern concrete. Aspdin’s version of Portland Cement differs considerably to the product with the same name today, though it represented a huge innovation in the path to modern concrete.

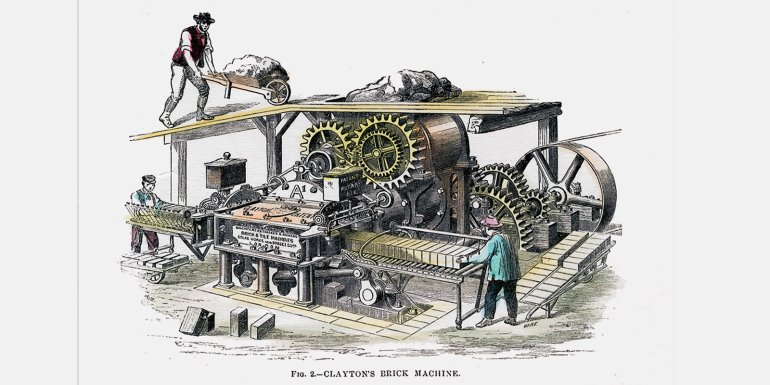

1855: Brick-making at scale

As the Industrial Revolution began to take hold, huge strides were made in terms of brick-making, particularly in terms of the rate of production. In 1852 New York, Richard A Ver Valen patented a brick-making machine, establishing his town – Haverstraw – as the capital of global brick production.

In the UK, the Bradley & Craven Stiff-Plastic Brickmaking Machine was also invented in 1852. However, Henry Clayton’s patented 1855 version is perhaps better known, capable of creating 25,000 bricks a day.

2024: Smart concrete

RAAC aside, we’ve seen some huge strides in terms of the quality of building materials used in the UK in recent years. Many of today’s buildings are now constructed with smart concrete, bringing a whole host of benefits.

Smart concrete is an umbrella term covering many different forms of concrete, each of which have their own associated benefits. Self-healing concrete, made with mineral additions or superabsorbent polymers to encourage autogenous repairs, falls into this bracket.

Another form of smart concrete includes self-sensing concrete, also known as self-monitoring concrete, which can sense stress, strain and damage within itself.

Smart concrete

The future…

Nasa researchers, in collaboration with Louisiana State University, are currently working to develop feasible robotic construction technology that could support life on the Moon. Materials such as sulphur and regolith, which are already available on the Moon and Mars, could be used to develop 3D-printed, waterless concrete. Who knows what lies ahead?

For more, visit instarmac.co.uk