In case of emergency

If you have a building that is greater than 18m or one that has at least seven storeys, and contains two or more residential units, then the Building Safety Regulator (BSR) may have already asked you to apply for a building assessment certificate and provide a safety case report.

The safety case report is a document that substantiates the control measures employed in the building to address fire spread and structure risks. Legislation requires that the report (and supporting information) is stored electronically and that updates are made on an as-and-when basis. Updates may be more frequent than you think, given the myriad of legislative issues now covering this subject.

The building also needs a Principle Accountable Person (PAP), who will need to ensure the safety case report is kept up to date and that the BSR stays informed of any safety-related incidents and design changes that occur. In addition, the PAP must implement a resident engagement strategy and ensure relevant safety information is communicated to the owners and residents.

At the time of writing, there is no guidance on how to prepare a safety case report. In contrast, the legislator expects relevant persons to develop their own strategy for this purpose. It will be interesting to see what the fire engineering fraternity produces, given that most have spent their entire careers working within a system that has shown little or no willingness to discuss or accept solutions that come with an explicitly stated level of risk.

Stated risk

Risk-based regimes that recognise that absolute safety is unobtainable are not entirely new. An example of such an approach would be the introduction of PAS 9980. The PAS replaced the government’s Consolidated Advice Note, which was withdrawn following criticism of the disproportionate treatment of risk. Section 0.3 of PAS 9980 states: “For some stakeholders there is no appetite to consider a risk-based approach and, for these stakeholders, the only satisfactory outcome is certainty in the performance of external walls in fire, with zero risk to life as the principal objective. The methodology in this PAS cannot be applied when such a view prevails.

“It is, therefore, assumed that this PAS will only be used in circumstances where a risk-based approach, implemented by a competent professional, is deemed acceptable to relevant interested parties, including those in devolved administrations.”

For the past 18 months, Semper has had a dedicated team that has been crafting a safety case offering using the three fundamental principles of risk assessment, which are: risk quantification, risk acceptance and risk management. The approach is computational and uses robust statistical data, fire engineering calculation, simulation procedures and random sampling techniques to assess the performance of building fire strategies.

The safety score is then adjusted using a point-scoring system and the Delphi technique to take into account the measures in place to manage ongoing risk. The approach applies to all buildings, whether they be new or old. It could also be used to determine the cost benefits of introducing a second staircase into a residential building that originally required only one. Semper’s long-term vision is to use the same methodology to design buildings’ fire strategies. This way clients will have a better understanding of fire-strategy robustness.

What if…

The requirements of the Building Safety Act 2022 in England (BSA) refer to the risk of fire spread and structural failure. In our works, we have taken this to mean the risk to occupants in the unlikely event that fire develops to such an extent that a full building evacuation is required. Exactly how ambient temperature structural risks are to be quantified is not 100% clear. However, we understand some form of cost benefit analysis is to be suggested to help determine whether additional control measures are required to further reduce the chance of disproportionate collapse.

In developing our safety case offering, the focus has been on what-if scenarios referred to on the GB Health and Safety Executive (HSE) website – for example, what are the potential consequences when a wall, floor or load-bearing element, designed in accordance with a British Standard, is attacked by a real building fire? Alternatively, what are the potential consequences if a fire starts in the middle of the night in an unoccupied flat and all fire containment measures (ie sprinkler and fire compartmentation) fail?

Our computational approach provides answers to these and many more questions. It is able to:

a. model human behaviour during the early and later stages of evacuation

b. determine the consequences associated with system failures

c. determine the consequences should load-bearing elements be challenged while evacuation is still underway; and

d. assess the pros and cons of various fire safety management regimes.

The starting condition for each what-if scenario stress test is summarised below:

- Stress test 1 – (Occupied | Detection | Mobile)

- Stress test 2 – (Occupied | Detection | Immobile)

- Stress test 3 – (Occupied | Detection fails | Mobile)

- Stress test 4 – (Occupied | Detection fails | Immobile)

- Stress test 5 – (Unoccupied | Detection); and

- Stress test 6 – (Unoccupied | Detection fails).

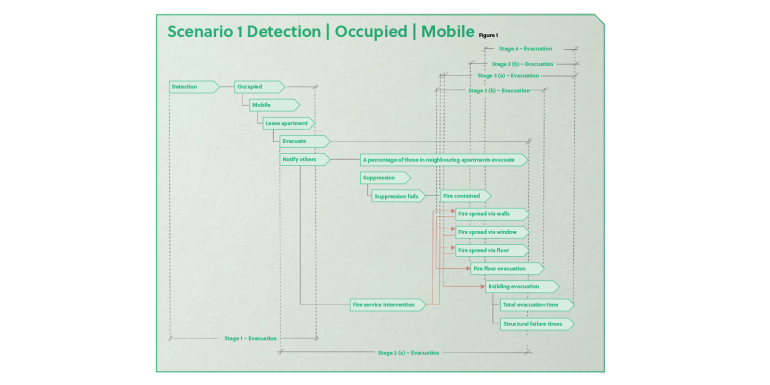

The structure of stress test 1 is shown in Figure 1.

The quantified approach we have developed means much of the subjectivity that comes with the simpler forms of risk assessment is removed. In our opinion, it is an approach that one would be more comfortable trying to defend in a court of law.

Risk acceptance

Acceptance of the safety score can be measured using comparative or absolute methods, as noted in BS 7974. In the context of this work, a comparative assessment would involve generating a safety score for the largest and most heavily occupied residential building in England and Wales. This score would then be used as the threshold against which all other safety scores would be compared. In the context of this work, an absolute assessment would compare the generated safety score with the safety level (or risk) individuals and society are willing to accept.

The comparative assessment is the simplest but most unattractive way to determine risk acceptance. This is because it assumes the measures in guidance provide an acceptable level of safety. This has never been proven. Unfortunately, analysis at an absolute level is also complicated and will remain so until someone with authority states what risk individuals and society should be willing to accept.

At this stage, we have reluctantly adopted a comparative analysis with a view towards moving to a more absolute approach in time. This will likely be done using an acceptance threshold that is an order of magnitude higher than research suggests. Refinements can then be made as more robust data becomes available.

Managing the risk going forward could involve extensive client involvement. To facilitate this, we have developed an online portal called Frank. The portal provides a space for all relevant safety case information to be stored and shared with BSR. More importantly, it allows the PAP to update the safety score in response to safety-related incidents, design changes occurring within the building, action plans coming from annual fire risk assessments and changes to building management regimes. This portal streamlines the compliance process, allowing clients to fulfil legal obligations with ease.

Having drafted several safety case reports already, we thought it would be interesting to list some of the barriers and obstacles we have come across so far:

- a general misunderstanding in all quarters as to the definition of the terms ‘safety’ and ‘risk’

- difficulties getting hold of relevant information because it is not known if it exists and, if it does exist, where it is stored

- a slight reluctance to pass on information for confidentiality reasons

- a slight reluctance to pass on information for fear of others potentially taking on a role in the future that was always their own; and

- people not understanding what a resident engagement strategy should look like or how one may work.

As we navigate the intricate web of building safety cases, it is evident that the industry is at a pivotal moment. The challenges posed by the absence of clear guidelines and the resistance among some to risk-based approaches necessitates a concerted effort from professionals to shape a safer built environment. If these types of methodology become commonplace, as we hope, then innovation will flourish, and all stakeholders will benefit in a way that fire safety guidance and historic working practices never allowed.

For more, visit sempergrp.com